The daughter of Russian Mennonite immigrants, Elsie K. Neufeld has written two non-fiction books: Dancing in the Dark: A Sister Grieves (Herald Press, 1990) and The Past Inside the Present (1996). She has taught life-writing classes in various venues with the guiding principle that “the ordinary is the extraordinary.” As editor, she edited several seniors’ anthologies; as personal historian, she has “midwifed” 20-some memoir projects; as eulogist, she has written nearly 20 eulogies – for family and strangers. Her essays and poems have appeared in many Mennonite publications as well as in Breaking the Surface (Sono Nis Press, 2000), Inside Poetry (Harcourt Canada, 2002), and a chapbook Grief Blading Up (2009). A resident of Vancouver, Elsie is on the board of Creative Non-Fiction Collective (http://creativenonfictioncollective.ca/)

The daughter of Russian Mennonite immigrants, Elsie K. Neufeld has written two non-fiction books: Dancing in the Dark: A Sister Grieves (Herald Press, 1990) and The Past Inside the Present (1996). She has taught life-writing classes in various venues with the guiding principle that “the ordinary is the extraordinary.” As editor, she edited several seniors’ anthologies; as personal historian, she has “midwifed” 20-some memoir projects; as eulogist, she has written nearly 20 eulogies – for family and strangers. Her essays and poems have appeared in many Mennonite publications as well as in Breaking the Surface (Sono Nis Press, 2000), Inside Poetry (Harcourt Canada, 2002), and a chapbook Grief Blading Up (2009). A resident of Vancouver, Elsie is on the board of Creative Non-Fiction Collective (http://creativenonfictioncollective.ca/)

OM: I see poetry as the most powerful, compressed, demanding form of expression in our language. In what other form does the author agonize over a single line, word, or punctuation mark?

EN: I think all writers, of all forms of writing, agonize over a single line, word, or punctuation mark. Hemingway, for example, said – and I’m paraphrasing here – find a single word that doesn’t belong. Vancouver writer and SFU professor Colin Browne, my writing instructor in 1985, said “find the sentence or phrase you’re most in love with, and delete it.” If that isn’t agony…

Writing, like a garden, is never finished. You plant; water; thin; and stake. You deadhead; prune; divide; and relocate the cuttings. Sometimes you store harvested seeds or rhizomes for the next season; sometimes you exhume and compost an entire plant and its offspring. The same applies to writing; editing is gardening words. Whether poetry or prose, every word, line, and punctuation mark matter. See, for example, the latest form of memoir: the six word memoir. Mine might be “Bought camera. Had a heart attack.” Add two words, and the memoir changes slightly. “Bought camera. That afternoon, had a heart attack.”

OM: Despite this, poetry is widely despised and financially unrewarding. Is it as simple as a judgement based on the length of a piece?

EN: Poetry is the music of words. Think of music, how many variations of music there are, and how rare it is to find a music-lover who appreciates all kinds of music. I don’t think poetry is despised so much as it is simply not appreciated, and too often not understood, not even by the poet who wrote it! Perhaps poetry is the equivalent of alternative music. And you’re right: poetry is financially unrewarding. I don’t know of a single poet who makes his/her living from published poems. No one chooses to be a poet for the financial reward; in fact, who chooses poetry? I believe poetry chooses the poet, and once you are chosen, and have heard the call, you let the poems flow through you, just as the ground doesn’t argue with what is planted in it. Poetry is still, for me, a spiritual expression, and I find it impossible to explain. If, per chance, some other soul receives my poems in a way that “grows it”, I’m grateful, and humbled, but that is not my aim. I write poetry because I cannot not write poetry. I’ve tried – oh, how I’ve tried – to quit poetry. But it refuses to let me go. As Boris Pasternak said, “I come here to speak poetry. It will always be in the grass. It will also be necessary to bend down to hear it. It will always be too simple to be discussed in assemblies.” Marion K. Stocking, editor of The Beloit Poetry Journal, said, “Poetry gives people a language for the things they can’t otherwise express.” For most people, poetry is a foreign language they don’t desire to learn.

OM: I often feel that poems are seen as training wheels, short stories as more advanced, and the novel as the pinnacle of achievement. Is this backwards? What are your thoughts on this?

EN: My thought on this is that writing, to some extent, is like dying. All mortals will die, but each person will die uniquely, at different ages, either foretold, or suddenly. There is no map for anyone; not even those who enter hospice care. One’s dying is as unique as one’s fingerprints. Forgive me for bringing death and dying into this interview, but I’m reading a book now, the way we die now by Seamus O’Mahony, and it’s influencing my thinking these days.

I think some are called to write poetry, others short stories, creative non-fiction, or fiction. Some manage all forms. Some begin with one, and are led into the other. Baron Wormser, Maine’s poet laureate in 2001, is a prime example. He earned his living as a school librarian, living in an area of Maine populated by woodsmen, truckers and back-to-the-landers. “He wrote fiction first, then poetry — no poetry workshops, no writers’ group, no master mentoring his work.”

OM: My poetry muscles have atrophied, and I fear that my other writing has suffered as a result. Is it important to switch between forms frequently to keep all muscle groups equally strong? Should we aim to be all-rounders, or is specialization the way to go?

EN: I can only answer that for myself. I am unable to write fiction. I switch between non-fiction and poetry. That said, my prose is, I’m told, poetic. There are very few writers who make a living on writing income alone.

OM: Is a Plan B actually damaging? Does it prevent full commitment to the writing life?

EN: We live in the world, and as my writer friend, Darcie Friesen Hossack says, “it’s all fodder.” Plan B may limit the time one has to spend on writing, however, I believe that writing is happening even when you’re not actually writing, so it may be Plan B can complement, not damage. Being fully committed to the writing life does not preclude Plan B. And, as you know, one can’t exist on water alone, so there is the reality of putting food on the table, and a roof over one’s head.

OM: What are you currently working on?

EN: As the last two years have been rather complicated by various family situations, I’ve been writing countless emails, which, upon rereading, could, and might, be distilled into creative non-fiction, memoir, and poetry!

What I’m currently working on, this past week, is a personal essay about an encounter I had with John Henry, a homeless man in Abbotsford at the end of a difficult day spent with one of my adult children, and then with my 90 year old mother, both of whom are in the throes of mental “unwellness”. I missed the August 5th submission deadline for The Malahat Review’s Constance Rooke Creative Non-fiction writing contest, so as soon as it’s done with me, I’ll submit it to their Open Season Writing Contest, deadline November 1, 2016.

Another project I continue to work on is a collection of interviews I did while strolling the streets of Abbotsford for a year (2013-14) as a flaneur. I was inspired by the Facebook HONY (Humans of New York), and am working on completing a manuscript Us is Them: elsiewhere in Abbotsford.

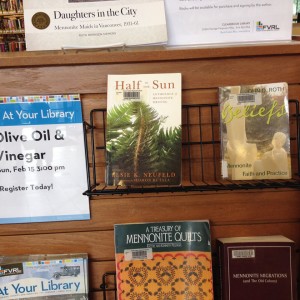

OM: Was compiling Half in the Sun like herding cats?

EN: Great question! If words are cats, then yes, it was about herding cats. In all honesty, working with 25 contributors, was exceptionally rewarding, and humbling. Our guiding principle as editors was poet Theodore Roethke’s lovely line, “We learn by going”, and so that’s what we did. If cats got out of hand, it was a learning opportunity.

EN: Great question! If words are cats, then yes, it was about herding cats. In all honesty, working with 25 contributors, was exceptionally rewarding, and humbling. Our guiding principle as editors was poet Theodore Roethke’s lovely line, “We learn by going”, and so that’s what we did. If cats got out of hand, it was a learning opportunity.

OM: As editor you had to deal with varying levels of professionalism, response times, willingness to revise, expectations regarding pay, and conflicting schedules. It sounds like an organizational challenge. Was that the case for you?

EN: Remember the book was published in 2006, ten years ago! And the anthology itself was five years in the making. My memory isn’t as it once was, but I’ll try to answer the question. As editor-in-chief, I was sometimes frustrated with the response time of one of the editorial team; the lesson learned from that was to never again work with a five-member team. Three maximum. With regard to the contributors, I believe they took their cue from our response to their queries, so there was never an issue with response times. Willingness to revise? I was pleasantly surprised by the openness to revisions from the established writers. The newer writers, I think, were so delighted to be included, that they were equally open. That said, most requested revisions were not demanded, although I do recall having a series of conversations with one contributor whose few publishing credits were religious periodicals. I felt the story was a very important one, and advocated for its inclusion, so it was accepted conditionally, and after several reminders of that, the contributor accepted the revisions. I think being professional in that instance led to good outcome. Re: payment. No one complained re the payment received: two copies of the anthology.

OM: Did you have a strategy for encouraging writers to submit?

EN: Submissions were primarily solicited from people I identified as “BC writers of Mennonite background”, writers I (and my team) either knew personally, or whose work I’d read, and those I discovered in literary magazines by their “ethnic” last names under “Contributors”. Call it sleuthing, because that’s what it was. A few writers found me via the Mennonite grapevine, and contacted me via email with, “I heard you are putting together an anthology…I live in Kelowna…”; several were recommended to me by well-established writers such as Andreas Schroeder, and Patrick Friesen.

OM: Was your plan to secure a couple of big name writers in the hope that others would be swayed by this? Or was the nature of the project enticing enough on its own?

EN: I knew from the moment the idea formed that it would be wise to include established writers in order to gain the attention of commercial publishers, and indeed, when I approached the publisher, and cited the names of the most well-known writers, he identified one who wasn’t yet included. I wasn’t surprised. That said, I felt the nature of the project – to showcase writers living in British Columbia of Mennonite background – was enticing enough as it had never been done, and, as it turned out, made Mennonite Literature history.

OM: What did you do to promote the anthology?

EN: Name it, and I/we tried it. I refer to myself as I seemed to have the most time of we five, and ended up doing the lion’s share of the work. We, the committee, brainstormed, of course; we collated our respective connections, added to those our contributors’, and cast the net wide. The anthology’s completion coincided with the tri-annual Mennonite Writing/s Conference, held that year in Bluffon, Ohio, so the book launched at that conference, with a plenary panel, and readings. We contacted newspapers: Abbotsford News, and the Times; BC Bookworld; Globe & Mail; Vancouver Sun; the Winnipeg Free Press, and every Mennonite institution in Canada and the US. We sent review copies to their journals and English department heads, and then Ronsdale Press contacted their libraries. There were fifteen readings (I attended every one), including three in Winnipeg, and one in Steinbach, Manitoba. There were readings in Kelowna, Chilliwack (2), Abbotsford (3), Langley, Vancouver (2), Victoria, and Prince George.

OM: How did you target Mennonites?

EN: My poet friend Robert Martens and I used to meet semi-regularly in Abbotsford, and one day I said to him, “I wonder how many other writers of Mennonite heritage there are in BC who meet like this?” And thus was the idea for the anthology born, and thus I began the search to find “others like Robert and me.”

How did we locate the contributors? Solely by their ethnic surnames, or from their self-identification as “half- or quarter-breeds.” Darcie Hossack’s mother was a Friesen. Harry Tournemille’s mother had attended a Mennonite Brethern church, and Harry himself had studied at a Mennonite Bible College, and entered the ministry, and six months later, quit. So, he was a mennonite by conversion, so-to-speak. Only a handful of the contributors are active church members. One was Bahai. Some are agnostics. Many, myself included, refer to themselves as “lapsed” or in church language, backsliders. In German, the word is “abgefallen.” Fallen. But that’s not a discussion to be had here. The question “Who/what is a Mennonite” is unanswerable, and continues to be asked by Mennonite academics, scholars, theologians, and church constituency – global now. By the way, I should add that we located over 50 writers, and then selected final contributors based on quality of work, or, in some cases, the potential we saw in their submissions.

OM: Did you go to or contact specific churches?

EN: Churches? I did not solicit churches for potential contributors. We were aware that few Mennonite churches would be interested as our target audience was not church-going Mennonites. We were looking for “literary writing” not “devotional writing material.” Ironically, our first reading occurred in the most “liberal” church in BC, where one of our contributors was a member. A rather awkward, very unexpected thing happened: one of the contributors with – how shall I put it nicely? – “church baggage” and for reasons still unknown to me, chose to read not from the anthology, but from a “piece in progress” that included countless F-words. A few, ironically, church-attending, contributors, snickered, while I sat embarrassed at the blatant disrespect in that setting. As I said, the church was the most liberal Mennonite church in BC, and the minister, with whom I later spoke, and to whom I apologized, was most gracious, and simply said, “We can’t control everything.” No judgement or fall-out whatsoever. That was the only church in which we held a reading. The very thing I wished to avoid – some conservative church-goer critiquing, or negatively judging some of the book’s contents – happened in reverse. But that doesn’t really answer the question, so I’ll move on to your next question.

OM: Did you advertise in Rhubarb magazine?

EN: Yes. Ronsdale placed an ad, and as John the Baptist foretold the coming of Christ, so, too, did excerpts of Half in the Sun appear in an all-west-coast issue of Rhubarb in 2015 which Leonard Neufeldt, Robert Martens, and I compiled and edited, and raised funds for.

OM: Promotion seems at odds with Mennonite culture. True or false?

EN: True, true, true. But this was not self-promotion. It was book promotion, and I was a very very proud editor-in-chief. Btw, did you know that Half in the Sun was rated among the top 100 books in the Globe & Mail for 2006? And that the anthology rode in BC ferry bookstores in 2007? If ever I see the book in a library or bookstore (yes, it’s still around), I place it, cover-side front – on the shelf. Shameless book promotion! No guilt, no apology, no second-guessing the countless hours of time spent on the making and promotion of that book. BC Mennonite writers were not on the Mennonite literary scene much at all until Half in the Sun! We made history! And what is history but promoting aspects of past?

OM: Do you think having a large number of contributors boosts the sale of an anthology. If every writer sells a hundred copies, that would lead to some decent sales figures, no?

EN: There is great potential for that, yes, but in reality? Established writers appear in many anthologies, so it’s understandable they don’t go out of their way helping with sales. Usually it’s the new and establishing writers who order extra copies; I seem to recall several contributors each ordering two dozen. The anthology in which my first poems were published included five prominent Canadian poets who each selected three poets they wished to promote. I sold fifty copies of that anthology, but the small press that published the anthology nearly lost her business. Most of the books sit in a warehouse. I did everything I could to promote Half in the Sun, and was told by the most established contributors that they’d never seen anything like it. I’m proud of that, too!

OM: Are there more anthologies in your future?

EN: It depends on how old I live. I work much more slowly, and my personal life is more complicated now, I think, than when I first began working on Half in the Sun. I enjoyed working with other writers; it is so true that “we writers are a tribe.”

OM: What anthology themes have you pondered?

EN: There is an anthology in the chute right now. The common theme is food, although not limited to being about Mennonite food; neither is it a cookbook, though several contributors included recipes. The project was near completion when my co-editor and I both had health set-backs, and she’s not yet ready to resume. I may, this winter, return to completing it. It’s almost finished, and how wonderful if it were out there in time for the next Mennonite Writing/s conference, to be held in Winnipeg in October 2017.

I’ve recently had two ideas: 1) an anthology of writing by contributors of Mennonite heritage who live with or have family members who live with mental illness; and 2) an anthology of writings by LGBT contributors or who have LGBT family members. At the Mennonite Writing(s) conference in Fresno, California in March, 2015, history was made when a group of LGBT persons presented a panel on their writings. It was wonderful, and one of the most popular panels at the conference. Long, long overdue!

This morning, after receiving an email from a writer of Mennonite heritage complaining of age-related memory issues, I thought of yet another potential anthology theme: “aging.” The writers of Mennonite heritage who put Mennonite writers onto the Canadian and US literary map are now in their late 60s and 70s, and are grappling with aging and its effect on their writing.

I think all three anthologies are a necessary shift from writing about the Russian Mennonite history.

OM: If you decided to do another one, what would you do differently?

EN: Whenever I read a book, I always first read the page of “Acknowledgements”. My next anthology would have no less than a full page of acknowledgements, with only my name on the cover and title page. Secondly, I’d find a patron to finance my time, or find some funding. I don’t have a money tree, nor buy lotto tickets, and have so much of my own writing still waiting to be planted into book form….

I enjoyed this article!

Unknown to all, while Ms. Neufeld and Mr. Martens met in Abby, I was busy churning out stories by the baker’s dozen in Chilliwack.

A list of what has been published so far – now that I have begun submitting to lit journals – is available here: en.gravatar.com/mitchelltoews

I would appreciate meet Ms Neufeld to se if she can write my life story . thanks

Hi Mario! I will pass your request on to her.