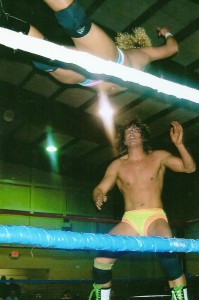

Tyler Dunning grew up in southwestern Montana, having developed a feral curiosity and reflective personality at a young age. This mindset has led him around the world, to nearly all of the U.S. national parks, and to the darker recesses of his own creativity. He’s dabbled in such occupations as professional wrestling, archaeology, social justice advocacy, and academia. At his core he is a writer. Find his work at tylerdunning.com.

The editor of The Fiddlehead‘s first creative non-fiction issue (No. 277) struggled to define the genre. I don’t like grey areas, and CNF resists black and white definition. What’s your definition?

This is a question I edge up against periodically and mostly when I find myself commingling in scholastic circles. That is to say, the academy would like to analyze and, in order to do so, needs a definition. This then opens the broader question of where creativity belongs amongst critics, and how well criticism lends itself to tutelage. And sure, I’ve had my frustrations, having been reprimanded by workshop leaders and peers for not investing more time in research—for not being more like, say, Didion—but good Christ, where is the fun in formula? Where is the fun in trying to force emotional truth into cold categories? My primary concern is the musicality of language (I could almost care less about content), so I take hard truths that I can’t seem to process otherwise and let prose guide me back through unreliable memory. It’s a dance, and dance, I think, is best performed in technicolor. People then liken what I do to poetry, have mislabeled my work as fiction, have written scathing reviews for bastardizing genres. So it goes.

We’ve invented words for it all—story, essay, novel, memoir, vignette, biography, historical fiction, et al.—and sure, these have their purposes, genre playing a key role for publicity departments, marketing teams, bookstore associates looking for a quick way to shelve a weekly shipment, the casual buyer, but when I sit down to write none of this is on my mind. I come to the page to suspend time, to enter a flow, to transubstantiate trauma. If the consumer can then relate through the creation, all the better, but I’m not here to clarify what is true or false, black or white, real or fake (after all, you’re talking to a former pro wrestler).

The first piece I ever had accepted for publication was a short story about finding baby Jesus in a grocery store dumpster. Someone asked me if it was true. What absurdity. But also, what legitimacy. Because I have found baby Jesus a time or two in a grocery store dumpster, but what literary gauge could ever measure such a miracle?

Since CNF is true, or mostly true, or more or less based on true events, or at least heavily influenced by real life (I’m having as much trouble as the editor), must you be careful to avoid any issues regarding libel when dealing with real life characters? Would you go as far as to get a written release? Is a verbal heads up good enough? Someone did brandish a weapon in your story, for example.

I used to be a vegetarian. My rational was that if I wasn’t willing to kill the animal myself, I didn’t have the right to eat it. I hold the same with real-life characters: if you aren’t willing to kill them, don’t eat them. My protocol has thus been to first send stories to anyone involved before publication. I’m not looking for permission or approval in this, only revealing the blade. I’m not in the business of backstabbing.

Speaking of armament, you bring up the example of someone brandishing a weapon. Maybe this is the better consideration: if a person doesn’t want to end up in my writings, perhaps they shouldn’t point handguns at me. That said, I don’t pursue written releases. Very rarely do I consider lawsuits or libel. To do so, I believe, is an unhealthy exercise in ego. Because to worry about libel is to first adhere to the hubris that people are actually reading your work. I mean, what a wonderful problem libel would be to have: for someone to mistakenly believe you’ve earned enough money through writing for them to legally pursue you! With that fear aside, I put the integrity of the story first.

Of course, I’ve lost a few friends this way—and honestly should have lost more—but that’s when you have to decide where your allegiance lies: with storytelling or with common courtesy. It’s not easy. This work isn’t for the well-adjusted. One of my favorite stories I ever wrote was a love letter to my dad, but it probably took me five years to finally share it with him (not until it was set for publication in my first book). It revealed unpleasant family annuls, and general household recollections from child’s-eye view, but it is perhaps the greatest gift I’ve ever given to him.

None of this is to say that recklessness is acceptable. Writing demands finesse and care. I eat my own liver over every sentence I scribe. But it’s not because I’m worried about the law. I’m worried about making my mother cry.

It’s not unusual to see all kinds of career shifts in the bio section of a journal, but the range of your shifts is quite astounding. I’ve gone from office clerk to tugboat deckhand. I had a friend who went from IBM to hairdressing. You’ve been an archaeologist, professional wrestler, social justice advocate, and academic. Do you use change to force growth as I do, or is change something that happens to you? Are you starting to settle into the truest, most natural you?

When I was fourteen I made the resolution to become a professional wrestler. This is also when I started contemplating killing myself. Both sent me down interesting paths. With the former, I had supportive parents that didn’t try to deter me, they only made me promise I never take a piledriver out of fear of paralysis. With the latter, it’s hard to care about a career path and retirement plan when you don’t anticipate living very long. Such a worldview introduced me to a lot of unique freedom. I chose a lifestyle that enlivened me, because to do otherwise would have resulted in self-slaughter. I studied religion in university because it intrigued me, not because it would ever financially sustain me, and that’s how I ended up digging through ancient Canaanite civilizations in Israel. I wanted to see every backroad of the United States, that’s how I ended up living in a van and public speaking across the country for a social-justice nonprofit. I’ve worked at a wedding chateau in Colorado, a natural history museum in San Diego, resided in the back of a furniture store for five years while writing my first book. I was never seeking change, but have forever been drawn to dark oddities that reveal the human condition of suffering. I chose to say yes to every absurd opportunity that came my way. This is how I’ve made my best friends, lived my wildest adventures, and instigated my greatest growth. None of it was by design.

So, am I my truest and most natural self? When I was younger I was plagued by longing. Now I’m distracted by nostalgia for those salad days. I will never be okay. But when I am lost in writing a story, the answer is emphatically yes.

Have you always been a writer, or did you take it up suddenly at the end of one of your other phases?

No, but I have always been a storyteller (my poor older brother, per our childhood bunkbeds, the suffer of my nighttime ramblings). The journey to writing was organic though, culminating at age twenty-seven, and in hindsight quite obvious.

I was first taught the craft of story in the wrestling ring. All pro wrestling matches are basically the same, just in the way that all literary stories are the

same. They follow a framework. In wrestling it goes like this: the babyfaces shines, the heel cuts the babyface off (usually by cheating and giving the crowd a reason to hate him/her), the heel applies the heat, the babyface has a couple of hope spots, then there is the hot comeback, then the two wrestlers take it home. It’s all jargon, but what I’m telling you is that there is a clear formula. That’s how I learned, through theatrical violence, to service a story.

same. They follow a framework. In wrestling it goes like this: the babyfaces shines, the heel cuts the babyface off (usually by cheating and giving the crowd a reason to hate him/her), the heel applies the heat, the babyface has a couple of hope spots, then there is the hot comeback, then the two wrestlers take it home. It’s all jargon, but what I’m telling you is that there is a clear formula. That’s how I learned, through theatrical violence, to service a story.

Next came my academic study of religion. What I love about the discipline is that it is the cohesive approach of all the soft sciences combined: history, psychology, sociology, anthropology, philosophy. What’s funny about this, in accord with your first question, is that no one has ever generated a uniform definition of religious studies, much like CNF. Lots of grey area. But religion taught me the power of storytelling, how it can guide the actions of entire people groups and shape the chronicles of history, for better or worse (mostly worse). A good example comes from a pretty standard Christian view of the natural world: if you are told humans being were set aside from other animals, that we have dominion over them, and that this planet is only a temporary home before transcendence (and that with the Second Coming the whole place is going to get destroyed anyway), why then would anyone ever worry about widescale anthropogenic degradation? Story becomes powerful under this scope. And dangerous.

Okay, so then I went to work for a social-justice nonprofit that truly excelled at delivering story through multimedia. I travelled the country showing films and giving presentations, and through grassroots means, we generated one of the most successful advocacy campaigns to date (at that point in time, we had the most viral video in the history of the Internet). All done through hip and Hollywood-esque storytelling.

With all this in consideration, by age twenty-seven, I was writing as a cathartic outlet, dealing with my depressive tendencies and processing existential confusion. And then it just clicked: I needed to tell stories. The answer had been in front of me the whole time. But I never wanted to be a writer, per se, I just knew it was my most accessible means to storytelling. I wasn’t a filmmaker, wasn’t a musician, wasn’t a comic, but I could write, so I selected that medium and dedicated the next decade into understanding it.

There seem to be many connections between professional wrestling and writing. Both involve a connection with story telling, building strong characters, being true to a form, attempting to perfect that form, and general entertainment. The majority of practitioners pursue their passion at great personal expense, living in relative poverty while a tiny percentage scoop up all the money and fame. Am I stretching this too far?

I touch a bit on this in the previous question, so I’ll try to avoid redundancy, but yes, pro wrestling and writing are both creative products born of storytelling and because of this they both adhere to certain standards of form (which, here in the States, is informed by Western expectations: i.e. rising action, climax, falling action, denouement.). They both take decades to master, with the result often being a simpler, slower, and more refined product (perhaps an Eddie Guerrero of wrestling and a Hemingway of writing); we spend our careers trying to hide the seams, to make both of the arts feel natural. When done right, goosebumps ensue. And to your final point, yes, both take their toll. What I like about writing though, opposed to wrestling, is that I will get to spend the rest of my life improving at it (excluding some unforeseen brain injury, of course), while with wrestling (like most athletic endeavors), from the first time you step in the ring you set a countdown clock. By the time you turn 35 the vessel for your storytelling, your body, is mostly broken and defunct.

The inequity of it all is maddening, but that’s also what makes it a gamble. If hard work and talent were assurances to success, then there would be no fun in chasing this dragon. That’s art: a roll of the dice, an acceptance of unending hardship, an irrational belief that you have undiscovered brilliance. The randomness allows me to overlook any actual failure. I fret the day, after a lifetime of toil, that I wake up and have to face my true mediocrity.

Societal hunger for the fighting arts has changed over the years. We’ve gone from boxing, to wrestling, to mixed martial arts. What does our current taste for MMA say about us?

We used to put lions in pits with humans and watch them get torn apart. Dog and cock fighting is still rampant across the globe. Stadiums fill to watch a matador slowly bleed out a bull. Tolstoy once said, “As long as there are slaughterhouses there will always be battlefields.” We are a violent species, and unlike any other species on the planet, we are violent for the sake of entertainment. What does this say about us? That nothing has changed.

However, one caveat I’d like to point out is that I don’t find pro wrestling to be a continuation in this logical sequence. I think wrestling ebbs and flows in its own cycles outside of boxing and MMA and this is because wrestling taps into a different part of our reptilian brains. You’d be better suited to compare wrestling popularity to daytime soap operas. I think you’d also be surprised to probably find that a Venn diagram of wrestling and combat sports demographics would have little central overlap. For example, I love pro wrestling but can’t stomach MMA—it’s way too violent for me. I hate bearing witness to obvious concussions, over and over. With wrestling though, I admire the grace and mechanics and fraternity and theatrics and the satire of reality. It’s story mixed with truth and child-like wonder. Like an SNL skit. A vaudeville show. Drag. It’s all the same unexplainable clarity you can’t seem to force into creative non-fiction.

If prevailing is about never giving up, how can a dedicated fighter know when it’s time to quit? Is there a sense of timing when to get out? Obviously, you don’t want to hang around until you are completely broken. Is there a general career life span? Is it over when the injuries start to pile up and linger? Is it over when the fighter feels pain everywhere, all the time?

There is no correct answer to this. In the business you see it all: people addicted to pain pills; people with memory loss from concussions; people that can’t get up or down stairs, who can’t get in or out of cars. I’ve known a person who died in the ring from taking a suplex a little too high on his neck. One of my heroes died at 38 from a heart attack. Another murdered his family then commit suicide, most likely the result of brain damage. What happens outside of the ring is not glamorous. But there is this unfortunate mythology that surrounds all creative endeavors about paying your dues—that you haven’t earned your time on the mainstage until you’ve wrecked your body taking meaningless bumps all over the country, working shows for little to no pay, sacrificing health and happiness along the way. I bought into this, believing I could suffer my way to the top. But the unfortunate reality hit me once I got into the business: it’s not about how hard you work or about talent. It’s often about politics, luck, and who you know. So I say stick around as long as you want, but don’t do it out of the notion that anything is owed to you or that any entertainment industry is inherently fair. You can easily grow old and irrelevant in the obscurity.

Hey King of Content, between the I’m Fuck*d envirozines, the fiction samples, the videos, and the national park summaries, your website is packed with at least 20 hours of things I want to consume. Well done! How active are you in the maintenance of your site? Do you have a team of people working on it? Has the exposure on your website resulted in new opportunities?

This is a kind question. Thank you. The site has been an organic endeavor. Back in probably 2011, when I was living with a brilliant household of filmmakers, graphic designers, sound engineers, chefs, and photographers, I faced much encouragement to start organizing my content (at that point I had a few dozen stories living on my laptop). So they set me up with a blog and then created a website for me via coding. This worked great for several years but became problematic once I needed a little more autonomy (not knowing code). So I spent a few hours learning Squarespace and then designed my own site. From there I started adding content as it was produced (stories, movies, podcasts, zines, etc.). I’ve been very lucky with the opportunities that have come my way and with the generous people I get to call my friends—they’ve all helped to make my content what it is. But as far as maintenance goes, it’s just me working on the site; I update stuff when it comes along, but now that it’s established, I don’t spend much time on it.

As for opportunities, gigs periodically come my way, but I can’t distinctively say the website is the reason. What it does help with is keeping an air of professionalism (I think all writers should have a polished site if they want to be taken seriously), offers for a cohesive platform to direct people when they are curious about my work, and allows for me to have a store to hustle my goods. I believe in the mantra, “set yourself up for the success you want to have.” Success and opportunities will (hopefully) follow hard work—don’t wait around for the opposite.

The short film based on A Field Guide to Losing Your Friends was an official selection at a variety of film festivals. Based on your experiences in the industry, how are book people different than movie people?

For the couple of years I toured my film, I mostly went to outdoor/environmental festivals and because of this I think it skews the kind of movie people with whom I was interacting—please take this into consideration with my answer.

Film people are a bit more fun. They take themselves less seriously. A big part of this, I think, which makes me jealous of their industry, is that it is more collaborative. When they show content and discuss their projects, it is often with a group of people: directors, film subjects, producers, etc. This always makes for better interviews and panels and general goofing. Film fests are dynamic, too, because they are weekends packed full of inspiring content. Writing, on the other hand, is a slowly consumed form of entertainment and, because of this, it makes it difficult to share collectively. Literary people are often more socially uncomfortable, too; less eager for the spotlight. I feel very fortunate to have a foot in both worlds.

Many of the writers I interview find self-promotion uninteresting and distasteful. Are you in that group? Publishers will do their best, but their writers are expected to be active and willing participants in the marketing and promotion process. If writers want to be read, I don’t see any way around this. What has been most effective in the promotion of your work?

I think of professional wrestling in this circumstance, specifically tag team matches. Here is the anecdote: when you are outside on the ring apron, and your partner is in the ring wrestling, it’s easy to forget that you have to still be present and reacting to the match (opposed to standing there recounting all the upcoming moves you are supposed to perform). Hence, if your partner is getting beat up, the rookie mistake is to show no reaction. The crowd subconsciously notices this. Because if you don’t care that your friend is getting kicked in the face, then why should they? Writing is the same way: you need to be the first one championing the work. Because if you don’t care, why would anyone else?

This isn’t then to say you need to be grotesque about self-promotion. But share your work. Be engaged with the literary community in some way, whether through blogs or social media or publication submissions or collaborative zines. But, and this is my biggest concern with promotion, you must be ethically conscious of the bandwidth you are taking up. Don’t ask for attention simply because you want/need/or have been told you are supposed to post once a day. We live in a digital age of information inundation that is destroying our brains. We aren’t meant to physiologically handle this much stimulation. So make ethical choices on how you participate. Also, only do what feels good. If you don’t like to tweet, well then don’t tweet. I used to prefer Instagram, but since all of its algorithm changes, it has felt far less fulfilling, so I’ve withdrawn.

My favorite way of staying engaged with my readership is through monthly newsletters. Here is why: the participants have given their consent, they only get one notification per month, and they can choose to open the email or delete it. Plus, I know everyone is receiving it in their inboxes. With Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, you have no idea who your posts are reaching (I’ve been told it can be less than 10% of your following).

It’s tough putting so much work into your craft and then not knowing how to reach an adequate audience with it. And the truth is you probably never will. But you also never know who your work is finding and how it is affecting them. Gandhi said, “Everything you do in this life will be insignificant, but it is very important that you do it.” So do the work. Market it if it feels right. But understand that there are very unfair forces at play: marketing is part of the system, playing the game is essential to the racket, it’s one eternal grind. Less talented writers will sell more books than you. Lazier writers will reach greater audiences and get more notoriety. Jealousy will ensure and bitterness will consume you. But extend grace. Pick the pen back up. And stop worrying whether “likes” are the solution.

Who has been most helpful in your development as a writer? How were they helpful?

This question could better be answered with a “What.” And I would say depression has been the most helpful tool in my journey. Because writing is really the only thing that currently alleviates my suicidal ideation and because of this the literary act has been a non-negotiable for about the last ten years. I write to stay alive. It’s that simple. Might sound a little cheesy, but don’t confuse it with “I live to write.” And I’m not going to tell you that it is my passion or that I was born to do it. That language is hollow. I just like pretty sentences, so I pursue them. And as a result, I feel gratitude, or try to, and that seems to be enough.

In my pursuit of pretty sentences, I have invested myself into books, trying to read one every week or two. I have no formal training as a creative writer and, as such, I let literature guide me. Here is a list of those that have influenced my work and how:

• Etgar Keret: he is the first one who made me want to write, showing me the intense power of flash fiction when done well.

• David James Duncan: the book River Teeth taught me the integrity of CNF.

• David Sedaris: he encapsulates a phrase I once heard, “Make them laugh and then break their fucking hearts.”

• Mary Shelley: she showed me how I can weave religion into my work in a secular way.

• Dave Eggers and Edward Abbey: I admire how they play with M dashes.

• Leslie Jamison: her essays are beautiful.

• Cormac McCarthy: no one sets tone quite like him.

• Donald Hall: he was a poet turned essay writer, and his poignant brevity is unmatched.

• Tom Robins: he dances with language.

• Tim O’Brian: talk about a guy who bends genre.

• Charles Bukowski: raw.

• Annie Dillard: our best observer.

• David Foster Wallace: I’ve found no better writer.

How important are connections in getting your work published?

With literary journals or online publications, not at all (unless somehow cover letter credentials are affecting this, but I don’t think that is the case). In terms of book deals and speaking opportunities, they are about 90% of the importance. It’s all about who you know. So start attending writing retreats and conferences (which unfortunately lends itself to the privilege of writing, because they aren’t cheap) and be strategic about it. Go to places where there are people who you want to meet. All of my big breakthroughs have come from these connections.

Is there such a thing as momentum when it comes to writing? Do you reach a point where your list of credits and contest wins pushes you up into the next tier of recognition?

You’ve caught me at a bit of a bitter point in my career, so my reflex is to say that I used to think momentum mattered. In 2017, I released my first book. This generated momentum for me and incredible opportunities. I thought I was going to ride this into further success, but then, around mid-2018 it all slowed down, as if I hit a field of mud. I’ve been slogging since. The problem is, now that I’ve tasted a little success, I know, in some ways, how unfulfilling it was. So getting the ball rolling again has been more difficult than ever. I’ve spent the last year trying to get back to stories that are meaningful to me, and not just ones that I think are going to sell. I feel less creative now, like something died inside of me, or at least is comatosed. A big part of this is because I tried to advance to a more financially lucrative tier by working with agents and meeting with publishers. They all had ideas of the direction my work should go and the content I should be producing. I lost myself in this and wrote hundreds of pages I didn’t really like.

That said, I do feel like you naturally progress through tiers and these might not always be obvious. For example, for years I would write articles for free for anyone who asked: blogs posts, articles, etc. This was good then because I didn’t really know what I was doing and didn’t feel much worth, but, one day, I just said, Hey, I’m not writing for free anymore. So I don’t. And that feels great. And I feel confident putting a price tag on my work because I’ve researched this business so ardently. I know where I am in the pecking order and I’m not going to let anyone take advantage of me. This is something I never learned in the pro wrestling industry. I let people walk all over me, felt trepidations negotiating a paycheck, and often times drove hundreds of miles to wreck my body in the ring for free. With writing, I can now at least afford the coffee shop lattes it’s costing me to generate the work.

Leave A Comment